Systemic Issues

If the principle of multiplication is so obvious, why doesn’t it happen more often in church life? How is it that our disciples don’t always go on to make other disciples, themselves? Why don’t the congregations which we started go on to start other congregations, as well? What’s the problem, here? Is our ‘multiplication theory’ too simplistic? Is it a little naïve to assume that it might be applied so easily to spiritual things?

An oft-quoted (but hard to attribute) leadership axiom states that ‘every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets’ [i]. If this is correct, then when we get results which we do not like (either by their presence, or by their absence), we should always ask how the system in place has either blocked more positive outcomes from happening, or enabled more negative outcomes to happen?

Photograph courtesy of @nci

There are many examples of such things in the Scriptures.

For example, in 1 Kings 12, following King Solomon’s high levels of taxation (which funded his grandiose building projects), the people approached his successor, King Rehoboam, to ask if he would lighten this heavy load. Rehoboam refused, the Northern tribes rejected his sovereignty, and the nation-state was fragmented. His unwillingness to reform an oppressive system led to irreversibly negative outcomes.

Conversely, In Acts 6, we read about a similar discontent among the early church. When it came to the daily distribution of food, the Greek speaking Jews were being overlooked by the Hebrew speaking Jews. Understandably, they asked the Apostles to fix this blatant racial inequality. The Apostles did so by asking them to choose seven people to manage the situation fairly, which they did by choosing seven Greek-speaking people. These decisions swiftly resolved the problem.

Systemic problems such as these could shed some light on why disciples and congregations are rarely multiplied in our local churches. Perhaps our ‘systems’ (i.e. our structures, policies, practices etc.) are simply ‘out of step’ with how multiplication works. If this is true, and we want to generate different outcomes, we would be well advised to review and reform our systems. However, a better understanding of why this might be true would help to justify such changes.

In human biology, multiplication (i.e. reproduction) happens through the ‘delight and tenderness of sexual union’. While God could have designed sex to be purely functional, He didn’t. Instead, He designed sex as one of the most enjoyable of all human activities. He wanted us to ‘be fruitful and multiply’ (Genesis 1.28), and He must have known that the best way to make us ‘willing partners’ in this plan was to make sure that the process was… fun.

Photograph courtesy of @dainisgraveris

However, would anyone in our churches say that process (or the ‘system’) by which we aim to reproduce disciples and congregations is… fun? Or, would they be more likely to say that it is bureaucratic, mechanistic and cumbersome? If our processes are more stressful than enjoyable, then something about our ‘ecclesial reproductive system’ is not fit for purpose. To return to our biological analogy, human couples with high stress levels sometimes struggle to conceive.

So, to enable the multiplication of disciples and congregations at a more rapid pace and generous scale, we must look to biology to inform our thinking, expectations and practices. Our ecclesial reproductive systems should be the most joyful element of local church life – not the most onerous. To enable this to happen, we should attempt to rid ourselves of every feature of our systems which suffocates that joy, and (to put it crudely) ‘puts us off’ the process.

So what might these systemic issues be? What do they look like, in our local contexts? These are difficult questions to answer without offending some, who might recognise their own church communities in the examples given. However, there is an axiom which states that ‘a bad system will beat a good person every time’ [ii] and, if this is correct, then to avoid identifying the glitches in our systems would not serve our people well. We must ‘grasp the nettle’, for their sakes.

#1 – Leadership Development

The first systemic issue is around leadership development. To explain this let us consider family dynamics again. Parents of small children will often tell them what to do (and rightly so), but this rarely works for very long. By the time children become teenagers, they resist such authoritative parenting styles, as to become mature they really need a more consultative approach. They need to move away from obedience and towards taking personal responsibility.

However, many churches hinder their members from becoming mature in this way. For example, when well-meaning church leaders assume too much responsibility, and neglect to allow others to try things out, they are unwittingly acting like the over-protective parents of small children. By doing so, they create systems which effectively infantilise their people, which obviously limits the growth and development of any potential leaders among them.

Photograph courtesy of @pawel_czerwinski

The capacity of such churches to multiply congregations is minimal, because they are so unlikely to develop their people to the extent that they might ‘step up’ to such a task, let alone to recruit and develop a team of leaders with whom they might share the work. A leadership development culture (i.e. desires, expectations and practices coherent with that goal) has to be embedded in any church which aspires to reproduce. A healthy relational system has to be in place.

The same is also true of the leadership development pathways within any given denomination, which can be more of a hindrance than a help. To go back to family dynamics, imagine a set of parents advising their adult children not to have children until their careers were well-established. In many cases (though of course not all), this policy would slow down the arrival of the next generation by a considerable amount of time.

Likewise, when denominations’ expectations of its leaders are too idealistic, their leadership development pathways drift into high cost and high complexity. This also slows everything down, and makes multiplication less likely. To make multiplication more likely, these pathways need to be as low cost and low complexity as possible. Affordability and accessibility are critical. A healthy developmental system has to be in place, as well.

#2 – Decision-Making

The second systemic issue is to do with decision-making. To continue with our family analogy, you would be hard-pressed to find many parents who allow their young children to make meaningful life decisions. Conversely, you would be disturbed to find many adults who allow their parents to make their meaningful life decisions for them! What is appropriate for the immature is not appropriate for the mature. Power is exercised in greater measure with age.

However, we sometimes fail to replicate this dynamic process in the church. While of course those who are untested in the faith should not be treated like the mature (1 Timothy 3.6), neither should the faithful be treated like the immature! When we limit opportunities for people to make meaningful decisions, we limit the wisdom that can only be developed by engaging in the process of decision-making, and in subsequent reflection thereon. We keep people stuck in immaturity.

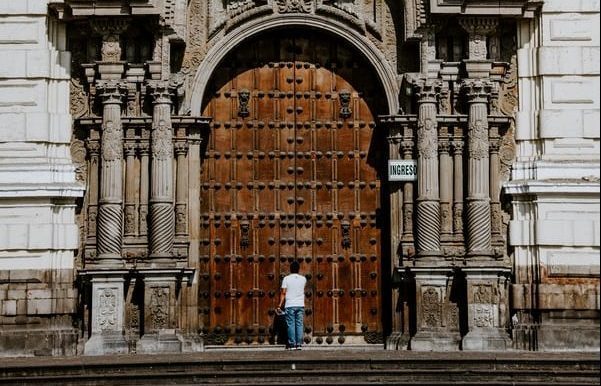

Photograph courtesy of @manunalys

Immature adults rarely make good parents. However, they could become both mature adults and capable parents, given the right support. In many church communities there are vast numbers of whom this is true – people who would be more than capable of making new disciples and starting congregations – but who never even dream of doing anything quite so ‘brave’. This is because the building blocks of appropriate self-confidence and sound decision-making are not in place.

In addition, it is worth pointing out the manifestation of these decision-making dynamics can vary considerably. Only in the rare minority of cases (in the UK) is there likely to be a direct and active prohibition of engagement in decision-making by those in positions of power. Rather, it is much more common for passive and implicit barriers to engagement to be present, such as a lack of communication, an absence of encouragement and a withholding of invitations to meetings etc.

Furthermore, the causal motivations for these behaviours in each specific person and context also vary significantly. For some, their motivation is to be considerate of others – they do not want to over-burden everyone with every issue which needs to be navigated. For others, their motivation is more ‘personal’ – they want to feel particularly important, which is less likely when more contributions from others are also being valued and affirmed.

Decision-making is a more complex issue than one might think, as issues of power, trust, reputation, validation, and even legacy, all come into the mix. When all these things are distributed liberally (as is entirely necessary for the multiplication of disciples and congregations to happen), it is somewhat threatening for those in power, as they are forced to ‘share the toys’. This is one of the reasons why ‘it’ (and thus, multiplication) happens so very rarely.

#3 – Money

The third systemic issue is to do with money. As with decision-making, in a family context access to financial resources almost always increases with age. Children may receive small amounts of pocket money, then larger amounts, then get paid for doing their chores, then finding part-time work etc. As adulthood approaches, the goal of financial self-sufficiency looms larger on the horizon, and for most people this does happen, eventually. The system works well enough.

Likewise, the financial system of most churches asks very little from its new members, but hopes that as they mature, they will become financial contributors. However, while most families function like this because they want the next generation to sustain itself, some churches function like this because they want the next generation to help sustain them. Families usually care about self-propagation; some churches care more about self-preservation.

Photograph courtesy of @adliwahid

Yet the purpose of the church is not to prolong its own life. We should be like healthy families, who invest all they can in establishing future generations. If this were the case, new disciples might be more encouraged to direct their giving towards making more new disciples, rather than towards maintaining the existing infrastructure. If this is not the case, it may be fair to question whether our current financial ‘systems’ have got a little bent out of shape.

In practical terms, our misguided financial systems can have a two-fold effect on our ability to multiply new disciples and congregations. Firstly, the activities which they generate (like proposals, meetings, and reports) often divert our attention away from what we could otherwise be doing (such as meeting new people, being hospitable to our neighbours, and developing common interests). Some would even call these distractions wasteful.

Secondly, they can prevent us from being able to do what we might otherwise do (like sponsoring an after school club, paying off a neighbour’s unexpected phone bill, or hiring a function room in a pub), because what money we might have fruitfully spent on these things has already gone on ‘keeping the show on the road’ (on things like photocopying, paying the organist, and repairing the roof). We can spend our money only once.

L.N. Smith once said: ‘Every dollar you spend . . . or don’t spend . . . is a vote you cast for the world you want.’ If our financial systems are not really helping us to multiply congregations, then they may well be hindering us from doing so. Thus perhaps we should more earnestly ‘throw off everything that hinders’ (Hebrews 12.1), and change what we can, so that we can do what we ought to. Our primary calling is not to manage money, but to make disciples.

In the late 1800s, Henry Venn outlined three operating principles which he considered necessary for establishing indigenous churches amongst unreached people groups: self-propagation, self-governance and self-funding. However, among many churches there is a deep-rooted reluctance to implement such principles, as is revealed by the aforementioned systemic issues. This must be due to something more than practicalities. Maybe it is a personal matter…

Notes

[i] See the following web-link for a discussion of the most accurate person to whom this axiom should be attributed: http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/origin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Feasible options include W. Edwards Deming, Paul Batalden, Arthur Jones and Donald Berwick.

[ii] Cited from the following web-page: https://deming.org/a-bad-system-will-beat-a-good-person-every-time/. Viewed on the 9th September, 2020.